|

Posted 6-6-11 |

One World, One Force

Arming the International

Community, Part I By Carl Teichrib, Chief Editor www.forcingchange.org - Volume 5, Issue 5 |

Index to previous articles from Forcing Change

|

|

||

|

Posted 6-6-11 |

One World, One Force

Arming the International

Community, Part I By Carl Teichrib, Chief Editor www.forcingchange.org - Volume 5, Issue 5 |

Index to previous articles from Forcing Change

|

|

||

On a recent radio show I was asked about the international implications of sending forces into Libyan airspace. Although I hadn’t been watching the news every minute of every waking hour, the question didn’t catch me off guard: R2P - the Responsibility to Protect (aka: Right to Protect).

Upfront, I don’t agree with Libya’s shyster government, one with a history of repression. Indeed, the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (Libya’s official name) has been led by an authoritarian ruler for too long. Yet, until a few months ago, Muammar Gaddafi and his government had been a darling of the international community.

In 2008 Libya held the presidency of the United Nations Security Council, then it took the lead in the UN General Assembly the following year. Libya was elected to the UN Human Rights Council and chaired the African Union, both in 2010. Today it’s a major shareholder in the African Development Bank and presides over OPEC. And in January 2011, Libya was commended by the the UN Human Rights Council in its Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review: Libyan Arab Jamahiriya - applauding the “country’s commitment to upholding human rights on the ground.”

Then came the demonstrations, the brutal government reactions, armed confrontations, a surge in refugees fleeing the nation - including refugee deaths in the Mediterranean, international posturing by world leaders, and air-strikes by a coalition that initially waffled between “overthrowing” or “not overthrowing” Gaddafi.

The Libyan crisis is ongoing as I write this article, and the endpoint is anything but clear. Regardless, the question from my radio host wasn’t difficult to answer: This action against Libya, either right or wrong, will reinforce the R2P agenda. In the words of the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect; “If the UN and NATO had failed to take stronger actions, we would now being [sic] questioning whether the commitment to RtoP holds any value.”[1]

We will elaborate-on and critique “Responsibility to Protect” in the final installment of the One World, One Force series. However, a short introduction is necessary as R2P represents the manifestation of “international authority” and “force.” Simply put, R2P holds that when a nation fails to properly safeguard its own citizens, the global community has the responsibility to actively intervene through the use of collective force. In the present environment this national failure includes genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and other similar crimes against humanity. Clearly, a moral high-ground frames the public and political perception of Responsibility to Protect, yet significant contradictions and concerns exist; including humanitarian intervention as a pretext for other geopolitical goals.

To wit, David Chandler, Professor of International Relations at the University of Westminster, recognizes that something bigger is at play - a technocratic version of international management under the rubric of “good governance.”

“For the UN, and for R2P as it exists today, it is not the intervention (or reaction) aspect that is central, but the continuum of international oversight that is crucial. The UN has turned the issue of humanitarian intervention, which in the 1990s threatened to undermine its authority - by questioning the sovereign rights of member states and UN Security Council authority over intervention - into an issue of international governance

that asserts the UN’s moral authority over both Great Powers and post-colonial states. Key to this has been the UN’s assertion of an administrative and technocratic agenda of ‘good governance’ as the solution to a range of problems, from development to conflict prevention.The R2P concept depends upon the conceit that non-political, technical and administrative experts co-ordinated through the UN, can understand, prevent and resolve conflict. This conceit only works through reducing social, economic and political problems to technical and administrative questions of institutional governance.”[2]

Professor Chandler’s observation isn’t without warrant. Whether he realizes it or not, R2P emanates from a deep-seated World Federalist desire, one couched in the idea of managing the international landscape through the technical and legal instruments of world law, world courts, and world force.

Timeline Prelude

In past articles I’ve alluded to the subject of R2P and a “world police,” and in July, 2001 I had the opportunity of giving a presentation on “collective security” during the Freedom 21 conference in St.Louis, MO. For myself, this subject has been of interest since 1995 when I read a Canadian government report advocating an international military, police, and intelligence apparatus - to be funded, in part, through a world tax on currency transfers. And although researching this concept has helped me understand the global puzzle better, I’ve been reluctant to write about it in a meaningful way. The main reason for this, I suppose, is knowing that the topic needs to be developed into a groundbreaking book.

Alas, I don’t have the energy or resources to pull-off a project of this size, but I realize that a timeline would be most helpful in catching glimpses of the larger picture. Therefore, the purpose of this “One World, One Force” series is straightforward: To demonstrate the continuation of a big idea - the dream of a global force to ensure global standards.

In presenting this topic as a timeline, please be mindful that the pieces may not all jive, as individual entries can represent different movements and circumstances. But a common theme exists:

1. A system of world law must be in place.

2. An international judicial system needs to be operational.

3. Nation-states have to comply with the global standard as established by world law and world courts. States that do not conform may experience punitive measures.

4. The International Community, therefore, must have an enforcement branch: An international police or military arrangement that can be used as an effective tool to maintain world order.All of this, we are told, is necessary for “world peace.”

Timeline: 1900-1945

*Source references are listed with each timeline entry. Note: This is not an exhaustive timeline.

1900: Germany leads an international navel expedition (the Eight-Nation Alliance) against China during the Boxer Rebellion. Dutch statesman and former War Minister, J.C.C. den Beer Poortugael, described the expedition as a “remarkable...sort of international gendarmerie.” - See, War Obviated by an International Police (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915) pp. 102-103.

1900: The Hague Conference of 1899 placed on the table a host of codifications regarding wartime behavior, and the Permanent Court of Arbitration was established to settle international disputes. In the spring of 1900 some of these legal arrangements came into force, thus opening a new century with the embryo of “world law,” even if it only pertained to war and settlement issues.

1901: The tenth Universal Peace Congress was held in Glasgow, Scotland. “It became the clearinghouse for information about the peace movement and now is affiliate with the United Nations.” ( www.indiana.edu/~nobel/peacecongress.html). World law and an international arbitration process were advocated by the Universal Peace Congress.

1901-1910: A series of arbitration treaties and other agreements are developed under the rationale of international settlement. The initial motivation for much of this stems from the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Elites of the day anticipate a new international order arising through world law.

1904: In Theodore Roosevelt’s State of the Union address (December 6), he asserts the independent right of nations, yet explains that if a country engages in “chronic wrongdoing” the United States may be forced to reluctantly play the role of an “international police power.”

These comments elevated the hope of an emerging international brotherhood. Later, in 1915, Roosevelt’s address served as a backdrop to the book, War Obviated by an International Police

(The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915).1905: World Organization is published. The author, Raymond L. Bridgman, proposes a “world unity” that would encompass an international legislative process and world court, a global consciousness, and a world military/police force.

- Raymond L. Bridgman, World Organization (The International Union/Ginn & Company, 1905).1910: President of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler, convinces steel-magnate Andrew Carnegie to establish the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Carnegie, who already hadaccess to American presidential leadership and had previously advocated a British-American Union, now had a substantial philanthropic tool available to promote internationalism across the board. “Mind Alcoves” were eventually set up in libraries across the United States to nurture a global worldview, and the exploration of international law and governance became bedrocks of the Endowment. By its own admission the Endowment was “an unofficial instrument of international policy” and through this organization, Nicholas Butler could act as the “purveyor of the international mind and minister without portfolio for world peace.” Butler arguably becomes the Endowment’s most influential board member until 1945.

- For “unofficial instrument,” see, Tax-Exempt Foundations, Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations, House of Representatives, 83rd Congress, Second Session, December, p.172.

- For the statement “minister without portfolio, see Michael Rosenthal, Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), p.218.

1910: During his Nobel Lecture, Theodore Roosevelt advocates for world federalism;

“I cannot help thinking that the Constitution of the United States, notably in the establishment of the Supreme Court and in the methods adopted for securing peace and good relations among and between the different states, offers certain valuable analogies to what should be striven for in order to secure, through the Hague courts and conferences, a species of world federation for international peace and justice.

Roosevelt adds: “Each nation must keep well prepared to defend itself until the establishment of some form of international police power...” He noting that a combination of countries working together might be the most acceptable way of obtaining this goal, and that “the ruler or statesman” who could bring these dreams to fruition would receive “the gratitude of all mankind.”

- Theodore Roosevelt’s Nobel Lecture, “International Peace,” was delivered on May 5, 1910. The full text of his speech is found at Nobelprize.org.1910: The New York-based World Federation League is formed. Although it’s short-lived, the organization was influential in the 1910 Congressional decision to study “universal peace.” [see below]

- Milestones of Half a Century: What Presidents and Congress Have Done to Bring About a League of Nations (No publisher, date appears to be 1917), p.31.1910: A resolution (H.J. Res.223) appeares before the US House of Representatives authorizing a Congressional Commission to advise on universal peace.

“That a commission of five members appointed by the President of the United States to consider the expediency of utilizing existing international agencies for the the purpose of limiting the armaments of the nations of the world by international agreement, and of constituting the combined navies of the world an international force for the preservation of universal peace, and to consider and report upon any other means to diminish the expenditures of government for military purposes and to lessen the probabilities of war.”

During hearings, Congressman Bartholdt tells the House that a movement already exists to combine the military powers of Great Britain, Germany, and the United States into a world force - an international police to uphold the legal decisions of the Hague.

“The work of world organization or world federation was auspiciously begun by the creation of the Hague court, and we do not propose to have it stop there, but must insist that modern conditions which impress all with the absolute interdependence of nations imperatively demand its early completion.”

The US Secretary of the Navy supported the idea in principle, for this international force was to be centered in a world navy. However, the US Secretary of the Navy did note that major hurdles existed.

Later, President Taft told this Congressional Commission he had invited leaders from other nations to respond “as to their willingness to cooperate with us” by forming their own committees, and thus to formulate a joint action “to make their work effective.” Finally, Congressman Bennet of New York informed the House that the British cabinet responded with favor - in fact, Sir Edward Grey, the UK Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, expressed that his government was ready to consider the idea.

- See, War Obviated by an International Police (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915) pp. 179-183, 220.1911: Arguing for an international arrangement for world peace, Dutch Admiral H.E. van Asbeck recommends that nations place “their entire naval armaments at the disposal of the international organization, thus throwing at once the full weight of their naval power into balance.” The Admiral suggests “a board of admirals is to sit at the Hague...”

In Great Britain, T.J. Lawrence (a judicial expert), writes that “war will endure, till overbearing and unscrupulous states are restrained by international tribunals and a strong international police force.”

- See, War Obviated by an International Police (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915) pp. 85-86, 89, 208.1911/1912: The World Peace Foundation, which had a special relationship with Andrew Carnegie and Nicholas Murray Butler, publishes a pamphlet titled International Good-Will as a Substitute for Armies and Navies. This text calls for the creation of a fully developed “International Court of Arbitral Justice,” an official “International Congress” with a “Code of International Laws.” All of this would be backed up by an International Protectorate and an International Police - “an international army and navy... at first having very limited and then with widening function, all under treaty arrangements.”

- William C. Gannett, International Good-Will as a Substitute for Armies (World Peace Foundation, 1911/1912), p.11.1912: In a speech before the Washington Peace Society, Robert Stein suggests various approaches to world peace, including a Trustee or League of Civilization - an arrangement whereby Britain, France, Germany, and the United States “would amply suffice to constitute an international police.”

- Robert Stein, An International Police to Guarantee the World’s Peace (World Peace Society, 1912), p.6.1912: Holland’s former Minister of War, J.C.C. den Beer Poortugael, advocates the distant but “perhaps not inaccessible” goal of “one international police army.” Under such a system, “the States only retain for themselves an army of police for the preservation of internal order.”

That same year, German professor of law, Walther Schuecking, explains that an international force will be needed to maintain “the whole complex of international law as codified at the Hague.” -

See, War Obviated by an International Police (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915) pp. 99, 201.1912: Nicholas Murray Butler’s book on internationalism is published; The International Mind: An Argument for the Judicial Settlement of International Disputes (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912). Butler links the evolution of world law as part of the Hague process and recommends a world police force.

1913: Frustrated by the Peace Conferences, Dutch law professor Cornelis van Vollenhoven argues that international law and a World Court can only be practical if an international police force exists, and that this force operate under a legal authority outside of national governments.

- See, War Obviated by an International Police (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915), p.54.1913: Funded by Andrew Carnegie, the Peace Palace at The Hague officially opens its doors. The Permanent Court of Arbitration (which formed in 1899) moves into the Peace Palace. Another feature for 1913 is the installment of the Peace Palace Library of International Law, which still exists today. The Peace Palace eventually houses the Hague Academy of International Law and the International Court of Justice. Many intellectuals and elites anticipate that the Peace Palace will become the hub for a World Authority.

1913: Andrew Carnegie tells an audience at the Peace Palace that the future of humanity rests in the idea of all nations working together “in which Fraternity reigns under the aegis of Peace.” This, he elaborated, should begin with “an Entente embracing three or four of the principal civilized nations...” Thus, a nucleus world authority would arise from the dominant national powers. Other lesser nations, he hoped, would soon join and thus secure world peace.

“These great powers should then engage to act in concert against disturbers of the World’s Peace, if any such should present himself which would hardly be possible from the moment when such an association as I have mentioned becomes an accomplished fact.”

- See, War Obviated by an International Police (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915) p. 185.

1914: Andrew Carnegie creates and funds the Church Peace Union, and thereby influences the Federal Council of Churches. In its first resolution, signed February 10th, 1914, the Church Peace Union called for international cooperation through “arbitration of international disputes.” The document stressed that the Great Powers inform the world of their desire to maintain peace on the high seas, for the “three Teutonic nations, Germany, the Fatherland; Britain, the Motherland; and the United States, peopled largely with their sons and daughters” are engaged in international trade and “possess for its protection the greatest part of the naval power of the world.” Thus, they have the right to forge a “sacred pathway of peaceful exchange, promoting the brotherhood of man.” The resolution is a call to eliminate war, and a thinly veiled justification for the “three Teutonic nations” to act as world police.

- Church Peace Union, Resolution Passed by The Church Peace Union: Founded by Andrew Carnegie, at its First Meeting, February 10th, 1914.

1914 (October 18): The New York Times publishes an interview with Nicholas Murray Butler. President Butler admits that the “international organization of the world already has progressed much farther than is ordinarily understood.” Butler tells Times readers,

- Nicholas Murray Butler, A World in Ferment (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1918), p.34, 36.“...the time will come when each nation will deposit in a world federation some portion of its sovereignty for the general good. When this happens it will be possible to establish an international executive and an international police, both devised for the especial purpose of enforcing the decisions of the international court.”

1914: Theodore Roosevelt; “What I propose is a working and realisable Utopia. My proposal is that the efficient civilised nations - those that are efficient in war as well as in peace - shall join in a world league... to act with the combined military strength of all of them against any recalcitrant nation...”

- See, War Obviated by an International Police (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915), p.150.1914: The Socialist Party of America drafts a proposed manifesto, Disarmament and World Peace. In it, the Party called for an international court, an “International congress... over international affairs,” and an “International police force.” Furthermore, the manifesto advocates a “Federation of the working classes of the world in a league of peace.”

- Disarmament and World Peace: Proposed Manifesto and Program of the Socialist Party of America, Dec., 26, 1914, p.3.1914-1918: The summer of 1914 witnesses the outbreak of World War I, engulfing Europe, parts of the Middle East and Africa. Called the “War To End All Wars” and the “Great War,” the cost in lives was substantial: 9-10 million deaths, approximately 20 million wounded, and another 7 million missing in action. The power of modern industry is unleashed on the battlefield, introducing aviation campaigns, chemical attacks, battle tanks and effective submarine actions, and the devastation of machine-gun nests.

Considered as a chivalrous adventure by many in its early days, the Great War rapidly turned into a meat-grinder of unimagined proportions. When it closed in November 1918, Europe was in shambles and previously Great Powers - such as the Ottoman Empire and Czarist Russia - had crumbled. Although not the first war whereby nations joined as partners against a common enemy (this occurred on both sides), the unprecedented scope of the conflict accentuated the need for global collaboration.

1915: A US-based movement comprised of political and business leaders forms the League to Enforce Peace. The purpose: to build momentum towards an international league. This “League to Enforce Peace,” if it came into existence, would have judicial and military powers to enforce world laws.

“As the evil-doer must be restrained by force in our local communities, so the evil-doer must be restrained by force in the community of nations. The force which is proposed to be used by the League to Enforce Peace, economic and military, is essentially a police force...”

- Enforced Peace: Proceedings of the First Annual National Assembly of the League to Enforce Peace, Washington, May 26-27, 1916 - With an Introductory Chapter and Appendices Given the Proposals of the League, Its Officers and Committees (League to Enforce Peace, 1916), p.7-8, 20.

1916: US President Woodrow Wilson endorses world organization,

“...the United States is willing to become a partner in any feasible association of nations formed... I feel that the world is even now upon the eve of a great consummation, when some common force will be brought into existence which shall safeguard right as the first and most fundamental interest of all peoples and all governments, when coercion shall be summoned not to the service of political ambition or selfish hostility, but to the service of a common order, a common justice and a common peace.”

- Milestones of Half a Century: What Presidents and Congress Have Done to Bring About a League of Nations (No publisher, date appears to be 1917), p.39.

1917: On December 28, the British Labor Party adopts a peace policy during the National Labor Conference, calling for “a supernational authority, or League of Nations... which every other independent sovereign State in the world should be pressed to join...”

- “British Labor’s Peace Policy,” Advocate of Peace, February 1918, p.48.

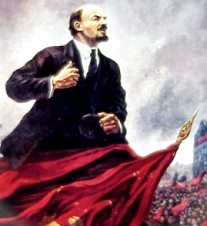

1917-1922:

A series of actions and uprisings culminates

in the October Revolution in Russia, witnessing the successful ascendency of

the Bolsheviks in 1917. Communism as a political ideology has found

expression through the Soviet system, and it was believed the world was ripe

for revolution (in 1905 Vladimir Lenin announced that an “international army

of socialism” was “preparing for the great and decisive struggle.”

1917-1922:

A series of actions and uprisings culminates

in the October Revolution in Russia, witnessing the successful ascendency of

the Bolsheviks in 1917. Communism as a political ideology has found

expression through the Soviet system, and it was believed the world was ripe

for revolution (in 1905 Vladimir Lenin announced that an “international army

of socialism” was “preparing for the great and decisive struggle.”

A little remembered side to this period was the multinational situation as it pertained to the Russian Civil War. On the heals of the November 1918 closure of World War I, American, British, and Canadian troops - along with forces from other nations - engage the Red Army and its factions on Russian soil. Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe, Finland and the Baltic region, the Ukraine, and the Transcaucasian zone are impacted. During this same timeframe, Communist revolutionaries in Germany sought to gain the upper hand during the post-war chaos (this situation was ongoing until 1923, with spill-over effects lasting another decade).

Allied intervention in Russia disintegrated, and by 1922 the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics was formally operational. The number of dead, wounded, missing, and homeless from the Russian Revolution and Civil War are unclear; however, it is estimated that 10 million lost their lives. Internal purges, terror operations, and extermination campaigns marked this bloody series of events.

The stage for global ideological conflict had been prepped. In the Communist context, the world is pitted in a gigantic struggle between the forces of capitalism and communism; with global capitalism aligning itself through a League of Nations, and communism rousing an international revolution through a world-wide army of workers and agitators.

Scott Nearing, an influential American socialist, wrote the following in his 1944 book, United World.

“Before the peoples of the world could join hands in a co-operative commonwealth, the bourgeois state must be destroyed through the conversion of the imperial war [World War I] into civil war. In place of the bourgeois state must come the worker’s state. That in turn must give place to a world soviet, with its planned, coordinated world life. Sovietism presented a working plan for a unified world.

The Russian Soviets in 1917 and 1918 broadcasted to the entire world their proposals for peace, bread and freedom under a world soviet system. The leaders of the movement wrote, talked and organized in term of an impending world revolution and the establishment of a world society.”

- Scott Nearing, United World (Island Press, 1944), pp.121-122.

1917: V.I. Lenin’s State and Revolution is published; “For the complete extinction of the state, complete Communism is necessary.” (p.78 of the 1969 printing). The approach is evolutionary; feudalism to capitalism, then a transitionary period - socialism, a lower phase of Communism - then Communism in its highest stage of maturity.

1918: US President Wilson gives his Fourteen Points speech. Point 14 is a call to form an association of nations within the context of political independence and territorial integrity.

1919: The Paris Peace Conference establishes the League of Nations and lays out reparation terms for Germany (which would later be used as fuel in the Nazi rise). National arms reduction and international enforcement obligations are part of the League of Nations’ Covenant. Although American leadership carried-the-day in creating the organization, the United States ultimately refused to join.

1919: A Special Meeting of the British Labor Party and Trade Union Congress passes a resolution calling for general, national disarmament and for the League of Nations to possess “whatever forces are necessary for police purposes.”

- Labour and the Peace Treaty (The Labour Party, 1919), p.23.1919: In Berne, the Independent Labour Party holds a meeting with the Socialist International on “International Socialism and World Peace.” While openly celebrating the Russian Revolution, the Berne Conference also supported the League of Nations as a global agency for military re-structuring and world organization; “The League of Nations should abolish all standing armies, and finally bring about complete disarmament... The League of Nations should create an International Court, which, by means of mediation and arbitration, would settle all disputes...”

- International Socialism and World Peace: Resolutions of the Berne Conference, February, 1919 (Independent Labour Party; Socialist International, 1919), p.4,

1920 - 1946: The League of Nations has its first sitting. Over the years it has some victories, but it’s failures and the weakness of the organization dooms it. In 1946 it is officially dissolved.

1920: The Communist International calls for “a parallel illegal apparatus” in capitalist countries in order to assist the Party at the decisive moment of revolution. A further appeal is made to parties wanting to align with the Third International; “[Every party]... must systematically demonstrate to the workers that without revolutionary overthrow of capitalism, no international arbitration courts, no disarmament, no ‘democratic’ reorganization of the League of Nations will save mankind from new imperialist wars.”

In other words, no true world state - with courts, disarmament, and an empowered League - will arise until capitalism is wiped out and the world socialist revolution is victorious.

- The Comintern, “The Twenty-One Conditions of Admission into the Communist International,” Readings in World Politics, Volume III (American Foundation for Political Eduction, 1952 edition), pp.164-165.1920: An article released by the Communist Party of Great Britain reads in part,

“The economic processes of capitalism lead, we repeat, to war. The political processes of capitalism, based upon its national and territorially structured State, cannot create peace. Peace can only come from an international Republic built up by a series of Federal Soviet Republics...

Is international peace and emancipation worth fighting for? If you think so the Communist Party needs you. It is the recruiting force, in Britain, for volunteers for the world revolution. It is the party which sharpens its revolutionary theory as a weapon to fight with. If you wish to end the war with Poland, if you desire peace with Ireland, India, Mesopotamia, Egypt, etc., join the Communist Party. It is linked up, through the Third International, with the revolutionary workers of every land. In your district there is a local recruiting branch. Link up with the local regiment of Red fighters. Become identified with the British battalion! And you will then be in the international army that is moving forward to Communism and Peace!”

- William Paul, “Minerals and World Power,” (Communist Party of Great Britain, 1920). See the archives at Marxists.org.

1921-1937: A series of League of Nations meetings, prep-conferences, and international gatherings occur over the issue of disarmament - particularly in terms of naval operations. Diplomatic dramas, debated treaties and pacts, and stalemates and debacles all mark these years of the League.

1923: H.G. Wells, frustrated with the Geneva-based League of Nations, writes; “I believe that the power to prepare for war and make war must be withdrawn from separate States... and that ultimately there must be a Confederation of all mankind to keep one peace throughout the world.”

“The League we desired was to have been the first loose conference that would have ended in a federal government for the whole earth. It was to have controlled war establishments from the start, constricted or abolished all private armament firms, created and maintained a world standard of currency, of labour legislation, of health and education...”

But, according to Mr. Wells, this international order wouldn’t require the immediate involvement of all nations, just the ones with the most power.

“If half a dozen of the bigger political systems of the world, or even two or three, could get together to sustain a common monetary standard, a common transport control, a common law court, a tariff union, a mutual defence system, and a common guarantee of disarmament, they would achieve something beyond the uttermost possibilities of this Geneva affair.”

- H.G. Wells, A Year of Prophesying (Ryerson Press, 1924), p.9,10,30.

1924: The year before, editor and philanthropist Edward Bok proposed the American Peace Award, and in 1924 publishes a collection of the 20 best plans. Ideas included a Technocracy or Organization of Scientists to oversee world affairs, the advocacy of a “unity in religions,” an organization for international Free Trade, an International Criminal Court, national courts operating under world law, the establishment of an international bureau of education, and a plan to bring American leadership into the League of Nations.

One proposal, number 6, was to “outlaw war” through a Declaration of Interdependence; pledging allegiance to world peace, education in world unity - “universal training in world citizenship,” establishing an effective World Court of International Justice, and an “Interdependent Force of Peace Police.”

- For all the plans and proposals, see Ways to Peace: Twenty Plans Selected from the Most Representative of Those Submitted to The American Peace Award (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1924).

1928: “The ultimate aim of the Communist International is to replace world capitalist economy by a world system of Communism. Communist society... is mankind’s only way out...” - a text released at the Sixth World Congress of the Communist International, September 1, 1928.

1932-1945: The National Socialist German Worker’s Party (Nazi) gains the largest number of seats in the Reichstag, then moves into a position of dominance in 1933. Germany, which had been greatly shaken by the armistice of 1918 and the industrial/economic collapse of the post-war years, finds a new voice in Adolf Hitler. Before World War II erupts, Nazi Germany engages in strategic diplomacy, arms building, and domestic infrastructure development

- and it sought a New Man through eugenic and racial programs. Thus, a significant part of the Nazi emphasis was on the Nordic ideal within a reordered Europe; including the concept of “Living Space.” In 1938 Germany crosses the boarder into Austria and then annexes the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia.

1935: British statesman Lord Lothian explains that world peace can only be obtained “by bringing the whole world under the reign of law, through the creation of a world state...” Lord Lothian clearly viewed the League of Nations as untenable to world peace, instead he called for a Federation of Nations with supra-national authority.

- Lord Lothian, “Pacifism Is Not Enough,” Readings in World Politics, Volume III (American Foundation for Political Education, 1952 edition), pp. 14-23.

1937-1945: Leaders from across Christendom call for a new international order. The Oxford Conference of 1937 acknowledges that States needed to adhere to enforceable world law. In 1939, the Provisional Committee of the World Council of Churches recommended “some form of international organization,” including an “effective deterrent” through the “collective will of the [international] community” (although it wasn’t agreed upon how force would be used). A similar call for a “new order” was issued by Pope Pius XII that year and the next. And during the World War II, the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America hosted a working commission under the chairmanship of John Foster Dulles (later to become US Secretary of State), to explore the basis of a “just and durable peace” through a new international order - including world government - and to rally support for such an organization when it formed. During the close and immediate aftermath of World War II, a number of church-based organizations and commissions assisted in securing the United Nations.

- Commission to Study the Basis of a Just and Durable Peace of the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America, A Just And Durable Peace: Data Material and Discussion Questions (1941).

- Dorthy B. Robins, Experiment in Democracy: The Story of U.S. Citizen Organizations in Forging the Charter of the United Nations (The Parkside Press, 1971).

- Martin Erdmann, Building the Kingdom of God on Earth: The Churches’ Contribution to Marshal Public Support for World Order and Peace, 1919-1945 (Wifp and Stock, 2005).

1938: F. Elwyn Jones publishes The Defence of Democracy (E.P. Dutton, 1938) His conclusion regarding Fascist aggression is the creation of a collective security Peace Bloc, and if Germany and Japan are interested in keeping the peace and advancing no further with war aims, they too can join. However, if aggression takes place, Jones recommends intervention by the combined militaries of the Peace Bloc.

1939-1945: Czechoslovakia falls under Nazi rule in early ‘39. Germany then demanded the Polish Corridor and, in conjunction with the Soviet Union, invades Poland. France and the nations of the British Commonwealth declare war on Germany: World War II erupts in Europe. In 1941 Germany invades the Soviet Union, opening what was arguably the largest land-based conflict of the twentieth century. America enters that same year via Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor (which was an extension of Japanese military reach stemming back to 1937 and the Second Sino-Japanese War). By the time this global conflict closed, upwards of 60 million perished - including millions in labor and extermination camps.

World War II raised the bar of human destruction to new levels, including technocratically energized concentration camp programs, catastrophic scorched-earth actions, and the wholesale destruction of cities (including fire-bombing and the first atomic attacks). Rocket power and missile technologies enter the lexicon of death.

1939-1945: A host of public and private organizations develop peace plans, push for “international organization,” and drum-up support for world order - and later the United Nations. These groups include the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Church Peace Union (established by Andrew Carnegie), the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, Americans United for World Organization, the Council on Foreign Relations, and Council on World Affairs. By the mid-point of World War II, the US State Department started working with many of these groups to formulate public opinion, particularly as it related to the 1944 Dumbarton Oaks Conference.

- See Dorothy B. Robins’ book, Experiment in Democracy (The Parkside Press, 1971),

1939: The first edition of Clarence Streit’s, Union Now, is published. As Europe finds itself engulfed in Hitler’s fires, Streit’s book offered a vision of unity: An international federation - a Union of Democracies. Streit first recommends a “Union of the North Atlantic,” including a “union of government and citizenship,” “a union defense force,” “a union customs-free economy,” “a union money,” and a union “postal and communications system.” This Union was to form “a nucleus world government.”

Besides forming a combined Union military/police apparatus, Streit suggests that,

“Our Union, we have seen, would be even more powerful in other respects. It would enjoy almost monopoly world control of such war essentials as rubber, nickel, iron, oil, gold and credit...”

Streit was a Rhodes scholar and corespondent for the New York Times. Toward the end of World War I he found himself attached to the US Intelligence Service and gained a “confidential position” to the American Peace Commission in Paris, where he had access “to many secret official documents.”

“I was in an unusual position to see daily what was really happening, and how little the press or public knew of this, and to see, too, from the inside how propaganda was being handled abroad and at home.”

The Union Now book turns into a campaign, and in 1940 Mr. Streit starts an organization: Federal Union Incorporated. By 1941, Federal Union had offices in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Ireland, India, and Argentina. Later the group changed its name to the Association to Unite the Democracies, and in 2004 it became The Streit Council for a Union of Democracies. During World War II, Streit’s work influenced politicians and key individuals, including pioneers of NATO and the European Union.

- Clarence K. Streit, Union Now: A Proposal for a Federal Union of the Leading Democracies (Harper & Brothers, 1940 edition), pp.4, 62-84, 119, 233.

1939: The Swiss Committee of the International Peace Campaign issues a memorandum: “we demand general disarmament and a League of Nations police force, set up as an executive organ of the new order based on international law.”

- Commission to Study the Basis of a Just and Durable Peace of the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America, A Just And Durable Peace: Data Material and Discussion Questions (1941), p.42.

1940: The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace publishes The New World Order, a select bibliography on “regional and world federation.” (Select Bibliographies No.10, December 12, 1940).

1940: A 5-point platform is released by the US National Peace Conference. The fifth point: “Work for some form of world government through which our own and other nations may achieve peace, justice and security.” The NPC institutes an “annual World Government Day” for November 11, “in place of Armistice Day.”

- See Dorothy B. Robins’ book, Experiment in Democracy (The Parkside Press, 1971), p.29.

1940: John F. Dulles and Clarence Streit pen a draft declaration giving the US President expanded powers to form a “Provisional Union” and to create a “common defence and to perfect some common military organisation.”

- As described in Martin Erdmann’s book, Building the Kingdom of God on Earth: The Churches’ Contribution to Marshal Public Support for World Order and Peace, 1919-1945 (Wipf and Stock, 2005), p.238.

1941: Clarence Streit’s second book, Union Now With Britain, advocates the joining of the United States with the British Commonwealth, thus forming a global power block including control over international seaways. Britain and America, Streit believed, would thus establish a world government.

“It is also true that in World War I the American people broadened the aim... to the establishment of world government. It is noteworthy that an American led in making each of the four experiments in world government that followed: Woodrow Wilson, the League of Nations; Samuel Gompers, the International Labor Organization; Elihu Root, the World Court; and Owen Young, the World Bank...

...we must also admit that it was mainly British support that enabled every one of those four invaluable experiments in world government - League, Court, Labor Organization, and Bank - to be made real, and not left on paper.

No others have done so much to bring about world government as we Americans and British have. No others are so qualified by experience in this field...”

- Clarence Streit, Union Now With Britain (Harper & Brothers, 1941), pp.123-124.

1941: An agreement between the USSR and Poland calls for a, “...new organization of international relations on the basis of unification of the democratic countries in a durable alliance. Respect for international law, backed by the collective armed force of all the Allied States, must form the decisive factor in the creation of such an organization.”

- Felix Morrow, The Class Meaning of the Soviet Victor, March 1943. See the archives at Marxist.org.

1941: The Atlantic Charter is signed in August between Britain and the United States, establishing an anticipated post-war context for common security, “...the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security.” (Article 8).

1941: Henry Ford endorses World Federalism in The New York Times (December 3): “They [nations] would need no armies and there would be no wars because nations would all be neighbors in the same federation.”

1941: The Declaration of the Federation of the World, a resolution before the North Carolina House of Representatives, in unanimously passed.

1942: The Allies of World War II officially form an alliance through the Declaration By United Nations. With the Atlantic Charter, this Declaration set the stage for a new post-war, international system.

1942: Peace Plans and American Choices is published by The Brookings Institute. The author of this report, Arthur C. Millspaugh - a member of the Council on Foreign Relations in the 1930s - looks at the pros and cons of different world order proposals. World Federalism isn’t considered practical; “It is difficult to see how, unless a miracle should happen, this age-old dream can be realized at the end of the present war.” (p.2) The choices explored are:

1) America On Its Own.

American Leadership: Playing a dominant role in developing world law and maintaining peace through a new internationalism. “To the practical support of our leadership we would bring power of three sorts - moral, economic, and military.” (p.10)a)

b) American Mastery: This stresses the economic and military strength of the United States, and “assumes a frequent, vigilant, and aggressive use of that power to maintain world order.”

(pp.15-15).c) Balance of Power: America would align itself within a world division based on two camps to maintain global equilibrium. “If one side were weaker than the other, the United States would throw its strength to that side, not to make war but to prevent the other side from ‘cashing in’ on its superiority.”

(p.23)2) Hands Across The Sea.

British-American Alliance: Britain and America would join in a collective system to ensure world order and peace. The United States would oversee the Western Hemisphere, the Pacific and East Asia. Britain would keep the peace in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. (p.30).a)

b) Anglo-American Federal Union: The United States and British Commonwealth would jointly create a new central government.

c) A Union of Democracies: America would join with a union of 15 democratic nations and form a central Union government.

(pp. 40-41).d) United Nations Cooperation: All of the nations fighting Germany and Japan constitute the “United Nations.” After the war these nations would remain in a cooperative arrangement, “a real international organization forced out of hard necessities...”

(pp.44-45).3) Regionalism.

General: A World Federation would have its powers decentralized in federated regions.a)

b) Western Hemisphere: Based on the existing US Monroe Doctrine, the Western Hemisphere would form itself into a region. Already the Pan-American system is in place. “Inter-Americanism, as well as the vital interests of the United States, requires and makes feasible an adequate system of military defense for the hemisphere...”

(p.55).c) Europe: Hitler’s idea of a European New Order was doomed, but a unified Europe could be achieved. A European Federation or Union would integrate Germany, and it would develop its own “peace system” with encouragement from the American government.

(pp.59-61).d) Asian Union: With the exception of Australia and New Zealand, the Asiatic nations would form some type of union, probably with China leading the way under a cooperative arrangement with Russia and India. The Middle Eastern countries, including Turkey and Egypt, “may take steps to perfect an Islamic association.

” (p.64).4) League of Nations: The League could be given a second chance with a mind towards reform in social and economic spheres.

5) A Stronger Association: This would be something between the League and a world-state. Such an association would have its own Executive Council and functions, but military power would not be granted independent of nation states. Nevertheless, the Association would have its own general staff to “prepare plans for the application of coercive measures.”

(p.90).“National armaments would be drastically reduced, being fixed by two sets of requirements: those of internal policing and those of international peace and order. The small nations would be restricted to their needs for internal policing. The great powers, in addition, would be permitted and obliged to raise and equip a part of the collective military force. Each of the national contingents would be subject at any time to call by the council.”

- Arthur C. Millspaugh, Peace Plans and American Choices: The Pros and Cons of World Order (The Brookings Institute, 1942).

1943: Famous contract bridge player, Ely Culbertson - an engineer with an interest in mass psychology and political theory - publishes his book, Total Peace (Doubleday, 1943). This volume provides a detailed plan on World Federation complete with a world president, global judiciary and legislative branches, and an international military based on the “Quota Force Principle.” Such a system, he argues in the book and in a special pull-out section, allows for nations tosufficiently protect themselves while placing a percentage of the country’s force in an “International Mobile Corps.” Culbertson explains that the planet should be divided into eleven Regional Federations, and that each Region would be represented in the World Federation.

The following text comes from the book’s pull-out insert,

“Could a communist-dominated bloc of Russia, Turkey, Germany, Poland, France, China and Japan, dominate the world? Without the World Federation they might, especially if the democracies were divided within or between themselves. But with the World Federation such a communist alignment would comprise only 38% of the world’s military power, against the 62% total of the Mobile Corps, the Anglo-Americans and the other contingents of the World Police.”

1943: James T. Shotwell, a member of Woodrow Wilson’s advisory group to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, publishes his essay “The Nature of Peace,” which called for an “International court,” “International legislative bodies,” and “Adequate police forces, world-wide or regional.”

- James T. Shotwell, “The Nature of Peace,” Beyond Victory (Harcourt, Brace and Co, 1943 - editor, Ruth N. Anshen), p.23

1943: A November transcript between J. Stalin and F.D. Roosevelt reveals a candid discussion of how the post-war environment could look. Roosevelt suggests a “world organization” built on the principles of the United Nations (the UN at this point is the Allied arrangement). This world body would have an Executive Committee consisting of the USSR, Great Britain, the United States, China, two European nations (apart from the UK), one South American and one Middle Eastern country, an Asian nation (besides China), and a member of the British Commonwealth. A second group of four primary nations would make up the Police Committee, which would have powers to act quickly and without the approval of the Executive Committee.

Stalin remarks that the Police Committee would have to be “a coercive organ.” Roosevelt explains that the Police Committee should be established first, then the Executive Committee (which would deal with non-military functions), and finally a General Organ in which “every country would be able to speak as much as it wanted, and where the small countries could voice their opinion.”

Stalin suggests two international organizations; 1) a European organization including the United States of America, 2) a Far Eastern body for the rest of the world. Roosevelt tells Stalin that this proposal coincides with Churchill’s idea, except Churchill was considering three world bodies: Europe, the Far East, and the Americas. Roosevelt tells the Soviet leader that America can’t enter a European organization as his nation wasn’t committed to the European war effort until Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

According to the transcript,

“S [Stalin] asks if in the event the world organization proposed by Roosevelt is set up would the Americans have to send their troops to Europe?

“R [Roosevelt] answers that that is not necessarily so. Should the need to use force against any possible aggression arise, the United States could make available its plans and ships, while Britain and Russia would have to send their troops to Europe. There are two methods of using force against aggression. If there arises the threat of revolution or aggression or any other danger of violation of the peace, the country concerned could be quarantined in order to prevent the fire which had started there from spreading to other territories. The second method is for the four nations comprising the committee to present an ultimatum to the country in question to cease its acts threatening the peace, with the alternative of that country’s being subjected to bombardment or even occupation.”

- “TRANSCRIPT OF THE TALKS BETWEEN STALIN AND ROOSEVELT, NOVEMBER 29, 1943,” as found in Tehran, Yalta, Potsdam: The Soviet Protocols (Academic International, 1970), pp.341-342.

1944: The European Conference of the Fourth International denounces all attempts at creating an international police force by the capitalists. However, the Fourth International endorses unconditional peace obtained through the Socialist United States of the world.

“Socialism or barbarism, that is the choice which humanity faces... Nothing less than the fate of all humanity is involved. Only the triumph of the world revolution can open the way to progress... Today as the new and tremendous wave of the revolution rises, the Fourth International will rally to its banner the best fighting forces of the proletariat and lead them to victory, to the victory of the Socialist United States of Europe and of the world. Our hour will soon strike. The future belongs to us.”

- The European Conference of the Fourth International, Theses on the Liquidation of World War II and the Revolutionary Upsurge, February 1944 (See the archives at Marxists.org).

1944: The second edition of Haridas Muzumdar’s well-endorsed book is released, The United Nations of the World. In this volume, Dr. Muzumdar bridges East-and-West in the advocacy of world government through an envisioned United Nations (remember, the UN as a replacement to the League of Nations hadn’t happened yet).

“We aim to work for the new order in which no nation shall enjoy unbridled sovereignty, which carried with it the right to maintain armaments and the right to make war and peace at will. Armaments, if any should be deemed necessary, shall be maintained by the United Nations of the World...”

- Haridas T. Muzumdar, The United Nations of the World (Universal Publishing, 1944), p.242.

1944: A delegation of American, British, Soviet, and Chinese leaders meet at Dumbarton Oaks, an historical setting located in Washington, D.C. This conference propels the embryonic United Nations system, including how the UN Security Council will be comprised. A considerable public relations campaign preceded the event, with a host of civic organizations and policy groups pushing for some type of “international organization” equipped to “keep world peace.”

Secretary of State Cordell Hull provides a summary of conference proposals and omissions, including the general outline for an “international organization” with a Security Council and Military Staff Committee; “National air force contingents are to be made immediately ready for ‘combined international action,’ with the Military Staff Committee assisting the Council with such plans and their application.”

- See Dorothy B. Robins, Experiment in Democracy: The Story of U.S. Citizen Organizations in Forging the Charter of the United Nations (The Parkside Press, 1971), p.170.

1945: A joint statement by a delegation is given to US Secretary of State Edward Stettinius. Point 4 states; “We recognize the need of military force, placed at the disposal of the United Nations Organization, to assure world security.”

Delegates include official members of the Church Peace Union, the Twentieth Century Fund, the National Peace Conference, the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, and Friends Peace Committee, and the American Association for the United Nations (among others).

- See Dorothy B. Robins, Experiment in Democracy: The Story of U.S. Citizen Organizations in Forging the Charter of the United Nations (The Parkside Press, 1971), pp.197-198.

1945: World Federalism is highlighted at the Dublin, New Hampshire Conference on World Peace. Point Three of the Dublin Declaration reads; “...in place of the present United Nations Organization there must be a substituted world federal government with limited but definite and adequate powers to prevent war, including power to control the atomic bomb and other major weapons and to maintain world inspection of police forces.”

1945: The United Nations Conference on International Organization is held in San Francisco, and in June the United Nations Charter is signed. On October 24 of that year, the UN Charter is officially entered into force. Article 42 of the Charter states;

“Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations.”

---------

In the decades to follow, the implications and applications of Article 41 have been debated, and a host of other programs and proposals for a world organization - with a world military system - have circulated. Some of these plans aspire for an empowered United Nations with the capacity to tax and police as necessary to ensure world peace.

The next installment of “One World, One Force” will examine the period from 1946 to 1989; From the operational start of the UN to the Fall of the Berlin Wall.

Endnotes:

1. ICRtoP briefing, Impact of Action in Libya on the Responsibility to Protect, May 2011, p.2

2. David Chandler, “Unravelling the Paradox of

The Responsibility to Protect,” Irish Studies in International

Affairs, Vol. 20, 2009, p.34.

Carl Teichrib is editor of Forcing Change, a monthly online publication detailing the changes and challenges impacting the Western world.

Note from Berit: May I suggest you subscribe to this great online magazine. This vital information will help us prepare for the challenges we will be facing in the years ahead.

Benefits of Forcing Change membership...

Membership in Forcing Change allows access to the full range of FC publications, including e-reports, audio and media presentations, Forcing Change back issues, downloadable expert documents, and more. FC receives neither government funding nor the financial backing of any other institutions; rather, Forcing Change operates solely on subscription/membership support. To learn more about Forcing Change, including membership benefits, go to www.forcingchange.org

Forcing Change

P.O. Box 31

Plumas, Manitoba, Canada

R0J-1P0